Commentary

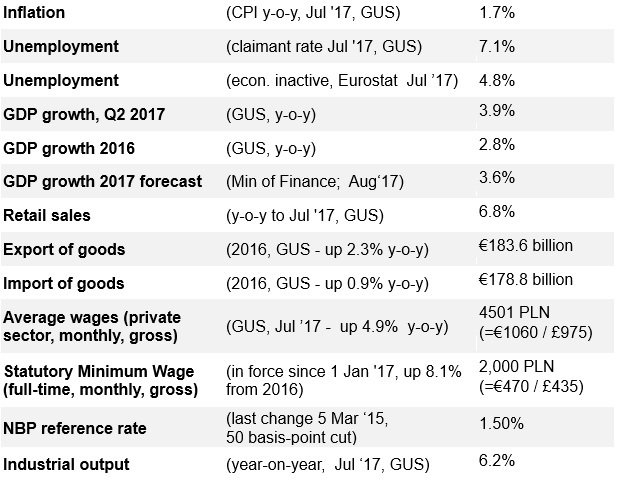

Poland’s Q2 2017 growth stayed strong at 3.9%, marginally lower than Q1’s 4.0% (although seasonal effects could be blamed for the slight deceleration). This is further proof that the slowdown witnessed in Q3 2016 was temporary, attributable to the poor take-up of EU funds at the beginning of the new financial perspective.

Successive macroeconomic forecasts are being revised upwards for this year; in July Standard & Poor’s and the Economist Intelligence Unit both predicted 3.6% growth for the whole of 2017, by August Austria’s Erste Bank had revised its forecast up to 3.8%.

Unemployment is at a record low at 7.1%, prompting employers across Poland to reassess their recruitment and retention strategies.

Concerted efforts by the Ministry of Finance to close down VAT loopholes which resulted in 53.4 billion zlotys of foregone revenue in 2015 are proving effective, with deputy premier Mateusz Morawiecki claiming to have clawed back some 15-17 billion złotys last year. The budget deficit is lower than planned, there is – for the first time ever – a small current account surplus. So all seems well…

However, concerns about the effects of political interference in the markets remain present among foreign investors in a number of sectors – retail and logistics (threats to Sunday trading are returning), banking (the ‘Polonisation’ of the sector), pharmaceutical (limits to advertising and selling OTC remedies), and foreign-owned media businesses. The construction sector still has issues with ease of obtaining planning permissions and poor public procurement procedures. But remaining sectors of the economy feel generally untroubled by political risk, and inward investment from the UK looks likely to rise as investors seek a lower-cost base within the EU.

Questions that investors will be looking at closely: will next year’s budget be able to withstand the higher social costs of the 500+ child-benefits programme and a lower retirement age? Will the Ministry of Economic Development’s plans to simplify bureaucratic procedures boost growth and counterbalance the additional social costs? Will the impending departure from the single European market of Poland’s second-largest export destination hit its industrial production and GDP? Will the Ministry of Digital Affairs be able to deliver an ambitious e-government project?

Poland has a strong, diverse and sustainable economy, based on the three strong legs of EU-funded infrastructure investment, growing exports of manufactured goods, robust domestic consumer demand and manageable private-sector borrowing.

Looking ahead for the next 15-20 years, Poland’s economy has the potential to continue to grow at a faster pace than that of western Europe, a point made in McKinsey & Company’s recent report Poland 2025: Europe’s New Growth Engine. Polish exports – linked to a great degree to Germany’s export powerhouse – will continue to grow at a faster pace than its GDP.

The fact that Poland reoriented its exports away from Russia and towards the EU back in the 1990s – and increasingly these days towards emerging markets – made its economy resilient to the shocks caused by the continuing Russian trade embargo. Poland is home to very little Russian investment and has only minor investments in Russia. While Polish exports to Russia are down by around a third compared to their levels in 2014, Poland has nonetheless managed to increase the value of overall exports over that same time. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia was Poland’s second-largest trading partner after Germany; now (Q3 2017) it has slipped to seventh place.

The effects of the conflict in Ukraine on Polish companies trading with Russia and Ukraine are easing as many have found alternative markets. Trade with Russia has long been haphazard, with embargoes on food exports, additional tariffs or non-tariff barriers being imposed then lifted at the drop of a hat. Exports to Russia have slowed (they represent just 2.8% of Poland’s exports this year compared to 5.3% in 2013). The opening of the LNG terminal in Świnoujście has reduced Poland’s dependence on Russian gas.

Poland will receive over €83 billion from Brussels in the form of structural and cohesion funds for the 2014-2020 EU budget perspective, of which some €28 billion is earmarked for transport infrastructure. This – like money from the 2007-2013 budget – will have a significant positive impact on the Polish economy, and will greatly improve transport around the country, to the benefit of business. However, the absorption of the funds is complicated by the new rules that have been introduced with the new budget perspective, along with changes of staff across the ministries that followed last year’s election.

Manufacturing output has bounced back strongly since the autumn of 2016; mainly driven by exports. Being Germany’s manufacturing outsourcing backyard, Poland’s industrial production is heavily dependent on Germany’s export-led economy. Germany now accounts for 27.5% of Polish exports (Q1 ‘17); German importers are taking up the slack from foregone sales to Russia. As well as Germany, the UK and Czechia have also seen significant rises in imports from Poland.

Trade figures for the first half of 2017 show that Poland’s exports and imports of goods are finely balanced, with a wafer-thin trade surplus of €0.5 billion.

The deflationary run that Poland has experienced since July 2014 came to an end, with consumer price inflation breaking into positive territory in December 2016, followed by a significant jump to 2.2% in February 2017, before falling back to 1.5% in June. The basket of prices had been falling gently (typically by less than one percentage point year-on-year) for two and half years. Russian food embargoes had the effect of dampening food prices in Poland as exporters seek domestic markets for their produce originally earmarked for Russia. Rebounding food and oil prices from a low base have put an end to deflation, as are wage rises caused by tightening labour supply. Wages, however, had been rising faster, with 6.0% growth in the private sector pay in the year to June 2017. The 8.1% increase in the statutory minimum wage on 1 January 2017 (from 1,850 zł to 2,000 zł) has also worked its way into the inflation figures.

[Note: The way Poland’s statistical office counts pay rises, industrial production and other indicators means that data is not collected from micro-businesses employing nine or fewer employees. This means that a true picture of average wages, productivity etc, cannot be gained as over 90% of businesses by number are not included.]

The Monetary Policy Council started loosening money supply by lowering base rates from a high of 4.75% (May 2012). In November-December 2012 and January-February 2013, the MPC made four consecutive 25 bp cuts, followed by a 50 bp cut in March 2013 and a further three 25bp cuts in May, June and July 2013, in response to weakening inflationary pressure. After three months of negative inflation, the MPC made a surprise 50 bp cut in early October 2014. The most recent cut was announced on 5 March 2015.

Demographics

Poland’s largest age cohort will reach the age of 35 this year (all 690,000 of them); this is Poland’s demographic high-water mark. By contrast, the number of 15 year-olds is a mere 350,000, the low-water mark. Over the next few years, the number of young people entering the labour market will continue to fall by an average of 17,000 a year.

However, the high quality of secondary education in Poland continues to encourage the BPO sector to invest in service centres in Poland, as does the high level of foreign language proficiency among younger Poles (Poland was ranked tenth in the world in the 2016 English Proficiency Index by language training company EF, with ‘high’ proficiency).

The shock to national accounts of large numbers of post-war baby-boomers hitting pensionable age in the early part of the next decade (65 year-olds born after 1952) will be made worse by the extremely low number of Poles of pre-pensionable age in the labour market. Only 28% of Poland’s over-55s are economically active (compared to 58% in the UK). The Tusk government raised the retirement age to 67 for men and women, though the new government has pledged to return it to the previous 65 for men and 60 for women.

Unemployment

From a high of 20.4% in February 2004, registered unemployment in Poland fell faster than in any major economy at any time in peacetime. By October 2008, it was officially 8.8% (though the BAEL measure used by Eurostat had Poland’s unemployment at 6.7% – this excludes those fictitiously registered as unemployed and working in the grey economy).

October 2008 marked the low point in unemployment in post-communist Poland, unsurpassed until June 2016. Compared to the situation in the UK, western Europe and the USA, Poland’s unemployment is lowest in the cities and highest in rural areas, with more than half of the long-term unemployed living in villages. By March 2013, unemployment had reached 14.3%, a new highwater mark, before starting to fall, down to 7.1% in June 2017 where it remains. However, Eurostat says that Poland’s unemployment, measured by economic activity rather than registered joblessness, stands at 4.8% (Apr-Jul 2017), suggesting that around one third of those signed on are actually economically active within the grey sector. Having said that, the gap between the GUS and Eurostat measures is shrinking, which suggests that the government’s attack on the grey sector is working.

There remain massive regional disparities between cities where unemployment is very low (Poznań 1.7%, Katowice 2.4%, Warsaw 2.5%, Wrocław 2.5%, Kraków 3.1%, Tri-City 3.3%) and many small provincial towns where it remains stubbornly in double digits. Szydłowiec, some 120km south of Warsaw, also in the Mazowsze province, holds the record at 25.8.%. Nearby Radom, a city of 200,000 people, also has high unemployment at 14.8%. Fruit-growing Grójec poviat has 2.6% unemployment (Jul 2017) reflecting the difficulties that employers have in finding fruit pickers.

The zloty

Although Poland had notionally signed up to joining the eurozone as part of its EU Accession Treaty, there was no mention of when, nor at what rate. To do so, Poland must first alter its constitution accordingly, which needs a two-thirds parliamentary majority. The current government is even more reticent than its predecessor to enter the eurozone; there is no pressure from the European Commission for Poland to do so.

The euro crisis has put any discussion of Poland abandoning the zloty on hold for the foreseeable future. Poland, therefore, lingers on the fringes of the EU’s central core – and – importantly for its manufactured exports – it can control the competitiveness of its currency.

The zloty, which had been rising rapidly in value against the pound, the euro and dollar in the four years after EU Accession, suffered a major depreciation in the aftermath of the October 2008 financial crisis. Between August ’08 and February ’09, the zloty depreciated by nearly 40% against the euro. This made Poland far more competitive for inward investment and for export, and was one of the key factors that kept Poland out of recession.

Since February 2009, the zloty climbed back, though not to the unsustainable level of 3.20 zł = € experienced in August 2008. Throughout 2010 and into 2011 the zloty held steady at around the 4.00=€ and 4.50=£ marks. The euro crisis, however, have knocked the steam out of the zloty’s stability. The wobbles on the markets caused by the threat of sovereign defaults in the eurozone and Hungary hit the zloty, knocking it back to 4.50=€ and 5.45=£. For much of 2012, however, the zloty has rebounded somewhat, stabilising at around 4.20=€ and 5.00=£ throughout 2013 and much of 2014. The Ukraine crisis barely affected the zloty’s stability vis-a-vis the euro. However, uncertainty as to the economic decisions being made by the new PiS government weakened market sentiment towards the zloty, which reached a low point of 6.09 against sterling in early November 2015. But then the EU referendum resulted in a dramatic fall in value of the pound. It remains below 4.65 złotys, the euro around 4.25 złotys.

UK-Polish trade

Trade between the two countries has been grown consistently since the end of communism, accelerating significantly since Poland joined the EU.

Expressed in sterling terms, 2016 was a record year for British-Polish bilateral trade ever; the value of trade in goods was £11.9 billion, nearly three times as much as before Poland’s EU accession. Last year, UK exports to Poland rose by 16.2% (to £4.2 billion) and Polish exports were up by 13.6% (to a record £9.4 billion). However, this is UK data in sterling; the fall in the value of the pound means that UK exports to Poland became more competitive, while Polish exporters gained at the expense of goods from the eurozone.

Poland has a large trade surplus with the UK (€7.4 billion – only with Germany does it have a larger one, at €8.4 billion). Brexit uncertainty in the first half of 2016 slowed the growth of trade between the UK and Poland. Bilateral trade between Poland and Czechia sometimes exceeds that with the UK, with a ding-dong battle going on as to which country is Poland’s second-largest export market (as of H1 2017, it was Czechia). Meanwhile the UK has slipped from eighth to tenth place in the ranking of Poland’s import sources, and is currently Poland’s sixth-largest bilateral trading partner (after Germany, China, Czechia, France and Italy).

Author: Michael Dembinski