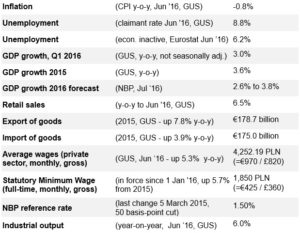

The big picture for UK companies new to the Polish market, key macroeconomic indicators updated each month.

The big picture for UK companies new to the Polish market, key macroeconomic indicators updated each month.

Commentary

The economy continues on its upward trajectory, albeit at a slightly slower pace than hitherto expected, reflecting concerns about possible effects of political interference in the markets. The threat of Brexit is expected to shave between 0.5 and 1% off Poland’s GDP in a full year.

Poland’s economy was in good shape as the Law and Justice government took over in the autumn of 2015. The question now is, in which direction will the new government take the economy? Will the budget be able to withstand the higher social costs of the 500+ child-benefits programme and the lowering of the retirement age? Will there be a strong focus on innovation, investment in infrastructure, and simplification of bureaucratic procedures? Will tax- and excise gathering be improved through greater efficiency and investmen

t in IT systems? Will the spectre of Brexit, the departure from the single European market of what had until the beginning of this year Poland’s second-largest export destination hit industrial production and GDP?

Risk remains in the form of new taxes to be levied against banks and larger retailers, and the consequent fall-out (higher bank charges, greater pressure on suppliers and their employees). The renewable energy sector (in particular wind) may be hit by new legislation, and plans to limit sale of agricultural land may end up hitting the very people the draft bill is intended to protect.

Nevertheless, Poland has a strong, diverse and sustainable economy, based on growing exports, infrastructure investment, domestic demand and manageable public- and private-sector borrowing. Although growth in industrial production was only up 0.5% year on year in March, macroeconomic forecasts remain strong to the end of 2016. Forecasts made by banks and other financial institutions for this year have been slightly revised downward, from around 3.5% to 3.0%, which is what year-on-year GDP managed to grow by in Q1 2016.

EU funds have also helped keep the economy buoyant. Looking ahead for the next 15-20 years, Poland’s economy has the potential to continue to grow at a faster pace than that of western Europe, a point made in McKinsey & Company’s recent report Poland 2025: Europe’s New Growth Engine. Polish exports – linked to a great degree to Germany’s export powerhouse – will continue to grow at a faster pace than its GDP.

The fact that Poland reoriented its exports away from Russia and towards the EU back in the 1990s – and increasingly these days towards emerging markets – should make its economy more resilient to any shocks caused by the continuing Russian trade embargo. Poland is home to very little Russian investment and has only minor investments in Russia. While Polish exports to Russia are down by around a third compared to their levels in 2014, Poland has nonetheless managed to increase overall exports over that same time.

The effects of the conflict in Ukraine on Polish companies trading with Russia and Ukraine are easing as many have found alternative markets. Trade with Russia has long been haphazard, with embargoes on food exports, additional tariffs or non-tariff barriers being imposed then lifted at the drop of a hat. Exports to Russia have been slowing (they represent just 2.9% of Poland’s exports in December 2015 compared to 5.3% in December 2013). The opening of the LNG terminal in Świnoujście has reduced Poland’s dependence on Russian gas.

Poland will receive over €83 billion from Brussels in the form of structural and cohesion funds for the 2014-2020 EU budget perspective, of which some €28 billion is earmarked for transport infrastructure. This – like money from the 2007-2013 budget – will have a significant positive impact on the Polish economy, and will greatly improve transport around the country, to the benefit of business.

Manufacturing output has picked up after a short contraction; once more it is driven by exports. Being Germany’s manufacturing outsourcing backyard, Poland’s industrial production is heavily dependent on Germany’s export-led economy. Germany now accounts for 27.1% of Polish exports (2015), compared to 25.1% in 2013; German importers are taking up the slack from foregone sales to Russia. As well as Germany, the Czech Republic and the UK have also seen significant rises in Polish imports.

Trade figures for the last year show that Poland’s exports and imports of goods are finely balanced, with a tiny trade surplus at €3.7 billion appearing.

Poland has been experiencing mild deflation since July 2014; the CPI basket of prices has been falling gently (typically by less than one percentage point year-on-year) ever since. Russian food embargoes are having the effect of dampening food prices in Poland as exporters seek domestic markets for their produce originally earmarked for Russia, while falling oil prices also are depressing prices. Further loosening of interest rates are needed to get closer to the National Bank of Poland’s inflation target of 2.5%. Wages, however, are rising faster, with a 5.3% jump in the private sector in the year to June 2016.

The way Poland’s statistical office counts pay rises, industrial production and other indicators means that data is not collected from micro-businesses employing nine or fewer employees. This means that a true picture of average wages, productivity etc, cannot be gained as over 90% of businesses are not included.

The Monetary Policy Council started loosening money supply by lowering base rates from a high of 4.75% (May 2012). In November-December 2012 and January-February 2013, the MPC made four consecutive 25 bp cuts, followed by a 50 bp cut in March 2013 and a further three 25bp cuts in May, June and July 2013, in response to weakening inflationary pressure. After three months of negative inflation, the MPC made a surprise 50 bp cut in early October 2014. The latest cut was announced on 5 March 2015.

Demographics

Poland’s largest age cohort will reach the age of 33 this year (all 690,000 of them!); this is Poland’s demographic high-water mark. By contrast, the number of 13 year-olds is a mere 350,000, the low-water mark. Over the next decade, the number of young people entering the labour market will fall by an average of 17,000 a year.

However, the high quality of secondary education in Poland continues to encourage the BPO sector to invest in service centres in Poland, as does the high level of foreign language proficiency among younger Poles (Poland was ranked eighth in the world in the 2015 English Proficiency Index by language training company EF, among the top ten with ‘very high’ proficiency). And successive PISA reports by the OECD show Poland ahead of many Western European countries in terms of literacy, numeracy and science.

The shock to national accounts of large numbers of post-war baby-boomers hitting pensionable age in the early part of the next decade (65 year-olds born after 1951) will be made worse by the extremely low number of Poles of pre-pensionable age in the labour market. Only 28% of Poland’s over-55s are economically active (compared to 58% in the UK). The Tusk government raised the retirement age to 67 for men and women, though the new government has pledged to return it to the previous 65 for men and 60 for women.

Unemployment

June 2016 was the month in which registered unemployment fell to match the lowest level in post-communist Poland, 8.8%, recorded in October 2008.

Falling rapidly from a high of 20.4% in February 2004, unemployment in Poland fell faster than in any major economy at any time in peacetime. By October 2008, it was officially 8.8%, though the BAEL measure used by Eurostat had Poland’s unemployment at 6.7% – this excludes those fictitiously registered as unemployed and working in the grey economy. October 2008 marked the low point in unemployment in post-communist Poland, unsurpassed until June 2016.. Compared to the situation in the UK, western Europe and the USA, Poland’s unemployment is lowest in the cities and highest in rural areas, with more than half of the long-term unemployed living in villages. By March 2013, unemployment had reached 14.3%, a new high-water mark, before starting to fall, back into single figures in August 2015, and down to 8.8% in June 2016. However, Eurostat says that Poland’s unemployment, measured by economic activity rather than registered joblessness, stands at 6.2% (June 2016), suggesting that around one-third (!!!) of those signed on are actually economically active within the grey sector. This compares with the UK, where registered unemployment is 5.3% while Eurostat’s measure of the economically inactive is 5.1% (January 2016). [Since October 2008, 0.5 percentage points of employment has been squeezed out of the grey sector.

The zloty

Although Poland had notionally signed up to joining the eurozone as part of its EU Accession Treaty, there was no mention of when, nor at what rate. To do so, Poland must first alter its constitution accordingly, which needs a two-thirds parliamentary majority. The new PiS government is even more reticent than its predecessor to enter the eurozone.

The euro crisis has put any discussion of Poland abandoning the zloty on hold for the foreseeable future. Poland, therefore, lingers on the fringes of the EU’s central core – and – importantly for its manufactured exports – it can control the competitiveness of its currency.

The zloty, which had been rising rapidly in value against the pound, the euro and dollar in the four years after EU Accession, suffered a major depreciation in the aftermath of the October 2008 financial crisis. Between August ’08 and February ’09, the zloty depreciated by nearly 40% against the euro. This made Poland far more competitive for inward investment and for export, and was one of the key factors that kept Poland out of recession.

Since February 2009, the zloty climbed back, though not to the unsustainable level of 3.20 zł = € experienced in August 2008. Throughout 2010 and into 2011 the zloty held steady at around the 4.00=€ and 4.50=£ marks. The euro crisis, however, have knocked the steam out of the zloty’s stability. The wobbles on the markets caused by the threat of sovereign defaults in the eurozone and Hungary hit the zloty, knocking it back to 4.50=€ and 5.45=£. For much of 2012, however, the zloty has rebounded somewhat, stabilising at around 4.20=€ and 5.00=£ throughout 2013 and much of 2014. The Ukraine crisis barely affected the zloty’s stability vis-a-vis the euro. However, uncertainty as to the economic decisions being made by the new PiS government have weakened market sentiment towards the zloty, which reached a low point of 6.09 against sterling in early November 2015. However, Brexit concerns weakened the pound even more, so at the end of July 2016, the pound is once more back to around 5.20 złotys, falling by over 8% from its pre-referendum levels.

UK-Polish trade

Trade between the two countries has grown consistently over the past 17 years; 2011 went on to become the best for bilateral trade ever; the value of trade in goods between the UK and Poland in 2011 (£11.4 billion) was nearly double that for 2007. However, while there was continued growth in the value of Polish exports of goods to the UK in 2012, the value of UK exports of goods to Poland slumped by 15% compared to 2011. 2013 saw UK exports to Poland rebound somewhat, though still not exceeding the 2011 values. 2015, however, while another record year in the value of Polish goods sold to the UK, saw a drop in UK goods sold to Poland.

Poland still has a large trade surplus with the UK (only with Germany does it have a larger one). Brexit uncertainty in the first half of 2016 has slowed the growth of trade between the UK and Poland. No longer is Britain Poland’s second-largest export market; it has slipped to third place (after Germany and the Czech Republic); and the UK has also slipped from eighth to tenth place in the ranking of Poland’s import sources.

Source: BPCC